Ask any yoga student what they’d like to focus on in class and there’s a reasonable chance that they’ll request—or perhaps demand—“core work.”

What many of us don’t understand is that it’s almost impossible to create a yoga sequence that doesn’t work the core in some way. Each time you bend twist or squat or otherwise shift your body weight, you rely on your core to create and maintain stability around your spine. These movements engage the muscles that surround your core in different ways: some will shorten, whether actively or passively, while others will lengthen. Sometimes the work is intense, other times it is subtle. We simply fail to recognize this as core work.

So what exactly is core work?

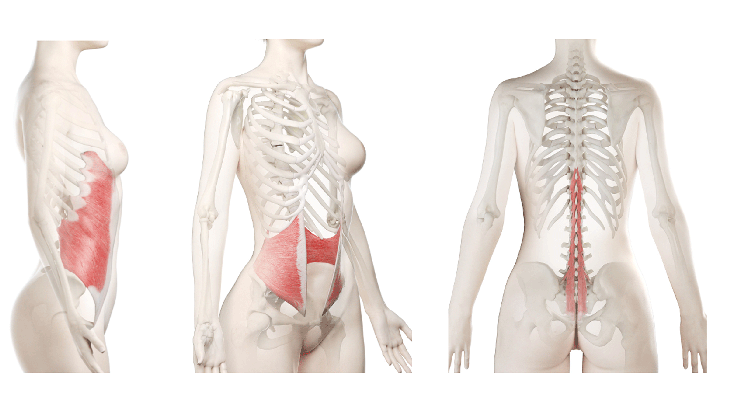

There’s no single approach to building your core that is complete. There’s nothing wrong with practicing poses that are obvious core strengtheners, such as Paripurna Navasana (Boat Pose). But true core work means working all of the muscles that surround your midsection, including the external and internal oblique abdominals, deep transversus abdominis (TVA), quadratus lumborum (QL), erector spinae, the psoas, even the pelvic diaphragm.

Comprehensive core work also allows your midsection to become flexible enough, through stretching and mobility exercises, to accommodate an array of body positions as well as the give and take of full, unrestrained breathing. This balance of strength and flexibility is how yoga postures prepare the muscles surrounding your core to work together without one region dominating the others. This creates a 360-degree cooperative tensioning system that supports you as you negotiate the many movements required by your practice as well as your everyday life.

35 yoga poses that are stealth core work

The following breakdown of common yoga poses, while not comprehensive, explains many of the less obvious ways that yoga supports core work. Once you start to notice the stealth strengthening and stretching taking place, you’ll understand how your practice can help stabilize all aspects of your core.

Rounded spine core work

Imagine yourself lying on your back and lifting your head and shoulders in a crunch or coming into Ardha Navasana (Half Boat Pose), in which your back and legs are lower and closer to the floor than in Navasana. We tend to think of these as core-focused poses because the scooped belly requires a strong ab contraction that you can feel.

But any rounded spine shape requires you to contract, and therefore shorten your anterior abdominal muscles. Holding Bakasana (Crane or Crow Pose) uses the same muscle group. Even coming into Marjaryasana (Cat Pose) requires a similar abdominal contraction. In “gentle” poses such as Cat, the contraction is automatic, but if you are looking for more core work you can be more deliberate about drawing your belly in or scooping your belly.

This effort can be felt primarily in the rectus abdominis and often leads to the satisfying burn or even shaking that many of us love to hate. You need this kind of strength to help you get up from the floor after lying down, to help you stay upright when kayaking or canoeing, and, to a lesser extent when you’re doing everyday tasks such as mopping the floor or raking the yard.

Poses that help your spine resist gravity

There’s a more subtle kind of anterior abdominal engagement that takes place in certain poses. This type of strengthening asks you to engage different core muscles so you can maintain the neutral spine that you experience in Tadasana (Mountain Pose). Unopposed, gravity would act on our abdomen and hips and cause us to sag into a backbend. Maintaining this alignment requires some contribution from the rectus abdominis, which you may or may not notice, along with subtle support from the deeper transversus abdominis to cinch in the waist.

Consider Plank, Chaturanga Dandasana (Four-Limb Staff Pose), Virabhadrasana III (Warrior 3 Pose), and the kneeling balance pose known as Bird Dog or Superman. Adho Mukha Vrksasana (Handstand) also requires this kind of abdominal engagement to maintain a tight plumb line but with a different relationship to gravity.

Balance poses and transitions

The real-world role of your core isn’t related to static strength. You require the kind of strength and stability that allows you to transfer your weight from one foot to the other as you walk, negotiate unstable or slippery footing, turn your head in response to noise, and make your way between sitting, standing, and many other positions—all without falling.

Your core is involved when you balance on one leg, as in Vrksasana (Tree Pose), Ardha Chandrasana (Half Moon Pose), Utthita Hasta Padangusthasana (Extended Hand-to-Big-Toe Pose). It is also engaged when you transition smoothly from one yoga pose to another as when you step forward from Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog) to High Lunge. Rather than rigid contraction, this kind of core work teaches us to embody strength in suppleness, which is the sthira (effort) and sukha (ease) referred to by Patanjali in the Sutras that helps us find balance as we adapt to situations in yoga and life.

Backbends that work against gravity

It can be surprising to learn that backbends are core work. Picture Salabhasana (Locust Pose) or Bhujangasana (Cobra Pose) with your hands lifted off the mat. Since they take the body into a position that’s typically associated with stretching the abs, they’re not typically understood as core work. But backbends require you to lift your head, shoulders, or legs against gravity which strengthens the muscles of the posterior core, mainly the erector spinae and QL.

Even holding yourself erect in poses such as Dandasana (Staff Pose) can create a slight backbend by engaging the muscles that hold you up against your postural tendency to slouch. In these poses, the posterior core muscles of your back contract and shorten while the anterior core muscles lengthen.

Backbends that work with gravity

In other backbends, gravity and the fixed position of your hands and feet tend to draw you deeper into the pose. Think about Udhva Hastasana (Upward Salute Pose), Ustrasana (Camel Pose), Urdhva Mukha Svanasana (Upward-Facing Dog Pose), and Urdhva Dhanurasana (Wheel or Upward-Facing Bow Pose). In poses like these, contracting the anterior abdominal muscles in their lengthened position (that is, eccentrically) creates the kind of support that lessens low back compression.

Twists and side bends

Any time you rotate your torso, you engage your lateral core muscles. This is especially the case when you initiate the movement from your core rather than relying on bracing your arm or leg against each other to initiate the movement. You can feel this kind of work in standing and seated twists such as Parivrtta Utkatasana (Revolved Chair), Parivrtta Anjaneyasana (Revolved Lunge), and Ardha Matsyendrasana (Half Lord of the Fishes).

In these poses, the external obliques on one side of the bodywork with the internal obliques on the opposite side draw one side of the rib cage toward the opposite hip. When you contract diagonally across your core from left to right contract, you get a twist. Conversely, when the left side contracts, you get a side bend to the left.

In side bends, both the internal and external obliques on one side and the corresponding QL contract together to shorten one side of the waist. You can feel this kind of engagement when you lift your bottom rib cage away from the floor in Vasisthasana (Side Plank). You can also feel it along your top rib cage when you hold your shape against the downward push of gravity while lifting your bottom hand off the support of your leg or the floor in Utthita Trikonasana (Extended Triangle Pose), Utthita Parsvakonasanaside (Extended Side Angle Pose), and Ardha Chandrasana (Half Moon Pose).

You use these same muscles much more subtly when you transition your body to face the long edge of your mat, for example, when you come into side-facing poses including Virabhadrasana II (Warrior 2) and Triangle.

Hip adduction

If you’ve ever taken a Pilates class, you probably noticed that a high percentage of movements involved squeezing your inner thighs together or into the resistance of a prop between them. That’s because some of the inner thigh adductor muscles share fascial connections with the pelvic floor to create a more complete core-strengthening exercise.

You can tap into this feeling of pelvic support or uplift by practicing Surya Namaskar A (Sun Salutation) with a block hugged between your thighs, by drawing your legs toward and into each other in Garudasana (Eagle Pose), or, more subtly, by trying to drag your feet toward each other without moving them (i.e. isometrically engaging the adductors) in standing poses including Chair, Warrior 2, and Utkata Konasana (Goddess Pose).

Breath work and supported poses

There’s perhaps nowhere in yoga that you explore that balance of effort and ease, not to mention the real-world importance of the core, more than pranayama or breathwork. Certain breath practices, among them Kapalabhati (Skull Shining Breath) or Bhastrika (Bellows Breath), require specific core muscles to be strong enough to emphatically engage to pump air out of the lungs. These techniques also require the muscles that surround the abdomen and rib cage to be sufficiently flexible to allow the torso to expand and make space for a full inhalation.

For this reason, true core work cannot be limited to building strength through muscle contraction. It must also build elasticity in these same muscles through mobility work and passive stretching. Consider gentle, passive backbends, such as the restorative version of Matsyendrasana (Fish Pose) and Supta Baddha Konasana (Reclining Bound Angle Pose), which allow the anterior abdominal muscles to slowly lengthen as you relax into the support of props and the floor.

Even passive forward folds, such as the standing forward bend Uttanasana, encourage the erector spinae and QL muscles of the posterior core to release. Likewise, passive and supported side bends and twists release the tissues of the lateral core. Every muscle that you want to strengthen also needs to be supple.

The next time you or your students ask for “core work,” keep in mind the array of poses and ways that can look and feel. There’s nothing wrong with generating a satisfying burn or quiver in your abs, but be aware that’s such a small part of what you need to support your yoga practice and your everyday life.

About our contributor

Rachel Land is a Yoga Medicine instructor offering group and one-on-one yoga sessions in Queenstown New Zealand, as well as on-demand at Practice.YogaMedicine.com. Passionate about the real-world application of her studies in anatomy and alignment, Rachel uses yoga to help her students create strength, stability, and clarity of mind. Rachel also co-hosts the new Yoga Medicine Podcast.