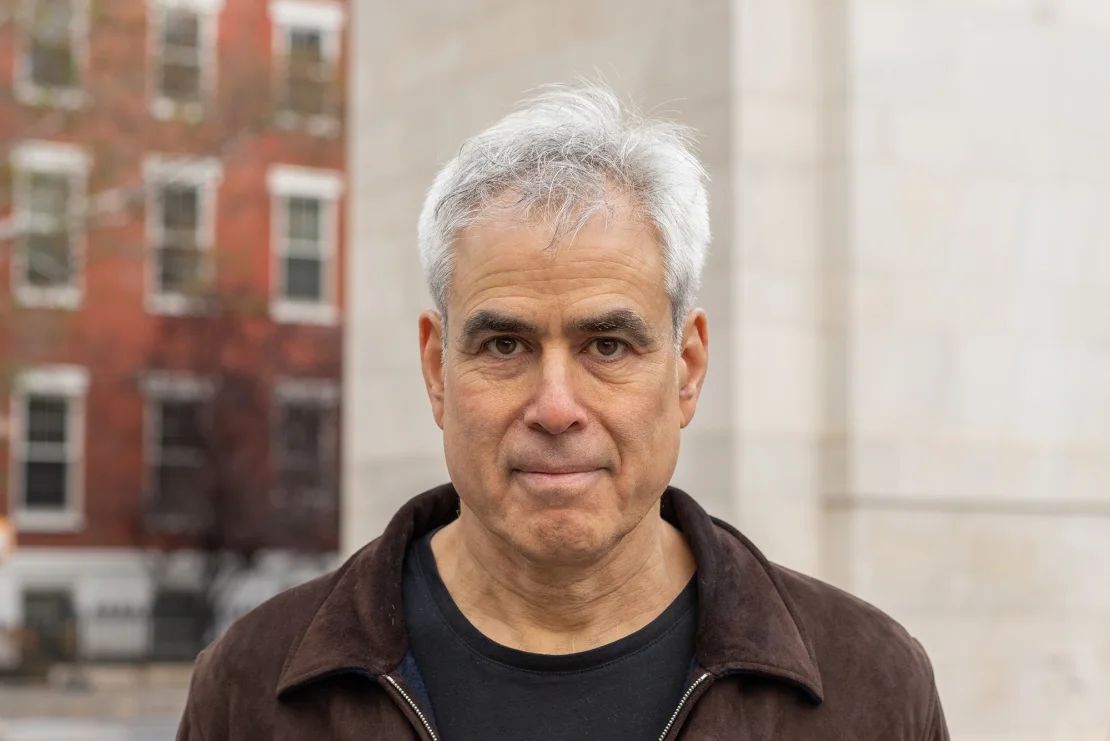

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt probably has become a pretty unpopular guy among teenagers over the last few weeks.

His new book, “The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness,” essentially calls for a revolution in how parents administer smartphones and social media to their teens.

Put simply, Haidt writes that kids should have little to no access to either until they turn 16.

While some have questioned the science behind Haidt’s thesis, Haidt argues the perspective is informed by years of research — investigations that depict climbing mental health struggles among American tweens and teens, and statistics that indicate many teenagers in the United States already are depressed or anxious in some way.

The American Psychological Association echoed his concern in a new report that calls out social media platforms for designs that are “inherently unsafe for children.” The APA’s report, released Tuesday, says that children do not have “the experience, judgment and self-control” to manage themselves on those platforms. The association says burden shouldn’t be entirely on parents, app stores or young people — it has to be on the platform developers.

But parents probably can’t count on developers, which leads to Haidt’s jarring conclusion: We’re at a tipping point as a society, and if grown-ups don’t take action, they could risk the mental health of all young people indefinitely.

Haidt, the Thomas Cooley Professor of Ethical Leadership at New York University’s Leonard N. Stern School of Business, has spent countless hours publicizing the book’s message since its March 26 release. CNN recently talked with Haidt about his data, the book and what lies ahead for parents and teens alike.

This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

CNN: How did we get ourselves into this predicament?

Jonathan Haidt: Kids always had play-based childhoods, but we gradually let that fade away because of our growing fears of kidnapping and other threats in the 1980s and 1990s. What arose to fill all that time was technology. In the 1990s, we thought the internet was going to be the savior of democracy. It was going to make our children smarter. Because most of us were techno-optimists, we didn’t really raise alarms when our kids started spending four, five, six and now seven to nine hours a day on their phones and other screens.

The basic argument of the book is that we’ve overprotected our children in the real world and we’ve under-protected them online. And for both halves of that, you can see how we did that thinking that it was going to be OK. We were wrong on both points.

CNN: What is some of the most startling data you found?

Haidt: The one that comes immediately to mind was the discovery that teenage boys used to have by far the highest rates of broken bones before the great rewiring of childhood. Before 2010, teenage boys were much more likely than any other group to go to a hospital because they broke a bone. Once we get to the early 2010s, their rates of hospitalization plunge, so that now teenage boys are slightly less likely to break a bone than are their fathers or grandfathers. They’re spending most of their time on their computers and their video games, and so they’re physically safe. But I would argue that this comes at the cost of healthy boyhood development.

CNN: Does this mental health crisis affect boys and girls differently?

Haidt: The basic facts about gender differences are that when everyone got a smartphone in the early 2010s, boys went for video games and YouTube and Reddit, while girls went more for the visual social media platforms, especially Instagram, Pinterest and Tumblr.

A second difference is that girls share emotions more than boys do. They talk about their feelings more, and they’re more open to each other. Girls’ levels of anxiety go up a lot in this period (the tween and teen years), as soon as they get hyper-connected to each other via social media.

Self-harm is a way that some girls have historically coped with anxiety, and those rates also went way up in the early 2010s. It used to be that (self-harm) was not a thing that 12- and 13-year-olds were doing, it was more older girls. In the 2010s, hospital emergency room visits (for self-harm) for 10 to 14-year-old girls nearly tripled. That’s one of the biggest increases in markers of mental illness that we see in all the data that I’ve reviewed.

CNN: You’ve said we’re at a tipping point in this crisis? Why?

Haidt: I think that this year is the tipping point for several reasons. In 2019, the debate was really getting started. Then Covid-19 happened, and that obscured previous trends. Now we’re a few years past Covid-19, past the school closures, past the masks, and what has become clear to everyone is that kids are not all right. And the data on rates of mental illness shows us that most of the increase was in place long before Covid-19 arrived.

Nowadays, in families across America, one of the biggest and most prevalent dynamics is fighting over technology. What I found since the book came out is that almost everybody sees the problem. Parents are in a state of despair. They feel like the genie is out of the bottle. They say, “You can’t put toothpaste back in a tube, can you?” To that, I say, “If you really have to do it, you’ll do it.”

When you look at the wreckage of adolescent mental health and you look at the increases in self-harm and suicide, you look at the declining test scores since 2012 in the United States and all around the world, I think we have to do something. My book provides clear analysis of the multiple collective action problems and of the four simple norms that will solve them.

CNN: What are the norms that will solve this crisis?

Haidt: No. 1: No smartphones before high school. We must clear them out of middle school and elementary school. Just let kids have a flip phone or phone watch when they become independent.

No. 2: No social media until 16. These platforms were not made for children. They appear to be especially harmful for children. We must especially protect early puberty since that is when the greatest damage is done.

No. 3: Phone-free schools. There’s really no argument for letting kids have the greatest distraction device ever invented in their pockets during school hours. If they have the phones, they will be texting during class, and they will be focused on their phones. If they don’t have phones, they will listen to their teachers and spend time with other kids.

No. 4: More independence, free play and responsibility in the real world. We need to roll back the phone-based childhood and restore the play-based childhood.

CNN: Rethinking smartphone privileges is a huge departure for many families. How do you convince parents to buy in?

Haidt: Elementary school is easy. If you’ve already given your kid a phone or their own iPad, you can take it away. Just be sure to coordinate with the parents of your kid’s friends so that your kid feels they’re not the only one. They can still have access to a computer; they can still text their friends on a computer. But if your kids are in elementary school, just commit to not giving them these things until high school.

Middle school is harder. Most middle school kids are entirely enmeshed in smartphones and social media. The key in middle school is to have some very severe time restrictions. The problem is the move from a couple hours of access a day to potentially having access all day long. That’s what does a lot of the kids in. Half of all American teens say they’re online almost constantly. If your kids already have these devices, I think you want to make some strict rules about when they have access to them.

CNN: What do you think will happen if we don’t change soon?

Haidt: Given that the rates of mental illness and self-harm and suicide are still going up, we don’t know where the limit is. We don’t know whether it’s possible to have 100% of our kids be depressed and anxious. We’re already getting close to half for the girls; we’re already in the ballpark of 30% to 40% having depression or anxiety, and about 30% currently say they’ve thought about suicide this year. Things are already really bad, and the levels could just continue to rise to the point where the majority of kids are depressed, anxious and suicidal.

This has enormous social implications, too. Because kids are somewhat sex-segregated online (they interact less with kids of the opposite sex), the situation is unconducive to heterosexual dating and marriage. I think the separation between boys and girls and their rising rates of anxiety are going to drive rates of marriage and heterosexual childbearing down much faster than they’ve been going — and they’ve been dropping for decades.

Lastly, I think there could be huge economic implications. Already, you have dozens of state attorneys general suing Meta and Snapchat because of the sheer amount of money that the states spend on psychiatric emergency services for adolescents. Another economic implication is that if we have one or two or three anxious generations where young people are afraid to take risks, our free market economy, our entrepreneurial culture, all the things that make the American economy so vibrant and dynamic will suffer. That’s why I think we have no choice. We (must) put a stop to this now.

Matt Villano is a writer and editor based in Northern California. Learn more about him at whalehead.com.